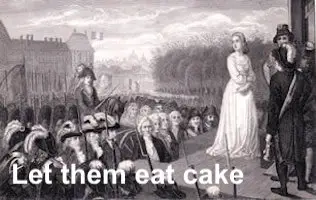

The origins of many English phrases are unknown. Nevertheless, many people would say that they know the source of this one. It is widely attributed to Marie-Antoinette (1755-93), the Queen consort of Louis XVI. She is supposed to have said this when she was told that the French populace had no bread to eat.

The original French is ‘Qu’ils mangent de la brioche’, that is, ‘Let them eat brioche’ (brioche is a form of cake made of flour, butter and eggs). The usual interpretation of the phrase is that Marie-Antoinette understood little about the plight of the poor and cared even less. There are two problems with that interpretation:

1. There’s no evidence of any kind that Marie-Antoinette ever uttered those words or anything like them, and

2. The phrase, in as much as it can be shown to be associated with the French nobility, can be interpreted in other ways, for example, it could have either ironic or even a genuine attempt to offer cake to the poor as an alternative to the bread that they couldn’t afford.

As to the origin of the expression, two notable contemporaries of Marie-Antoinette – Louis XVIII and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, attribute the phrase to a source other than her. In Louis XVIII’s memoir Relation d’un voyage a Bruxelles et d Coblentz, 1791, he states that the phrase ‘Que ne mangent-ils de la croûte de pâté?’ (Why don’t they eat pastry?) was used by Marie-Thérèse (1638-83), the wife of Louis XIV. That account was published almost a century after Marie-Thérèse’s death though, so it must be treated with some caution.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s 12-volume autobiographical work Confessions, was written in 1770. In Book 6, which was written around 1767, he recalls:

At length I recollected the thoughtless saying of a great princess, who, on being informed that the country people had no bread, replied, “Then let them eat pastry!”

Marie-Antoinette arrived at Versailles from her native Austria in 1770, two or three years after Rousseau had written the above passage. Whoever the ‘great princess’ was – possibly Marie-Thérèse, it wasn’t Marie-Antoinette.

Her reputation as an indulgent socialite is difficult to shake, but it appears to be unwarranted and is a reminder that history is written by the victors. She was known to have said “It is quite certain that in seeing the people who treat us so well despite their own misfortune, we are more obliged than ever to work hard for their happiness”. Nevertheless, the French revolutionaries thought even less of her than we do today and she was guillotined to death in 1793 for the crime of treason.