The life of Riley

What's the meaning of the phrase 'The life of Riley'?

'The life of Riley' is an easy and pleasant life.

What's the origin of the phrase 'The life of Riley'? - the quick version

There's not enough evidence to be 100% certain of the origin of the phrase 'the life of Riley' but it is probable that it derives from the life of a real person - Willy Reilly of Sligo, Ireland.

What's the origin of the phrase 'The life of Riley'? - the full story

The phrase came into common usage around the time of WWI. The first printed citation of 'the life of Riley' (with the easy/carefree meaning of the phrase) that I have found is from New Jersey newspaper The News, May 1910:

Henry Mungersdorf is living the life of Riley just at present.

Quotation marks are usually added to phrases that the readership might be unfamiliar with. There are none in the above citation so it's reasonable to suggest that 'the life of Riley' was known to the New Jersey populace in 1910.

It might seem strange that this expression originated in the USA rather than Ireland. However, there were probably more Rileys in New York then in Dublin at that date. Many of these would have migrated to look for a better life in America and some of them would have found it - and hence lived the life of Riley.

The phrase was much used in the military, especially in WWI. The first known citation in that context is in a letter from a Sergeant Leonard A. Monzert of the American Expeditionary Forces 'somewhere in France', an extract of which was published in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle on 26th May 1918. In the letter Monzert wrote that he and his pals were 'living the life of Reilly'.

Other similar letters from US servicemen claimed to have been living the life of Reilly while at war in France. How much truth there was in the letters and how much was propaganda to reassure the folks back home isn't clear. With hindsight we can be sure that any soldier's life during the First World War was no picnic.

There had been various Victorian music hall songs that had referred to a Reilly who had a comfortable and prosperous life; for example, there's the 1883 song, popularised by the Irish/American singer Pat Rooney - Is That Mr. Reilly? It included in the chorus "Is that Mr. Reilly, of whom they speak so highly?". Like most other Irish songs of the era, it played to the Irish audience - this one with a dash of anti-Chinese racism thrown in for luck (the Chinese were 'Reilly's' principal competitors for manual work in the USA at the time):

I'll have nothing but Irishman on the police

Patrick's Day will be the fourth of July;

I'll get me a thousand infernal machines,

To teach the Chinese how to die,

Another Irish/American song, George Gaskin, was popular in New York around the same time. He was called 'The Silver-Voiced Irish Tenor", although audiences must have been rather forgiving in those days, as surviving recordings of him sound like a knife being drawn across a plate. His 1897 song, The Best in the House is None Too Good for Reilly, elaborated on the whimsical idea of a wealthy Irishman being treated lavishly:

He's money for to pay,

So they let him have his way,

The best in the house is none too good for Reilly.

So, while the idea of a notional Irishman living the high life was current in late 19th century Ireland and America, the phrase 'the life of Riley' isn't found until the early 20th century.

So, who was Riley/Reilly and why was his life so enviable?

The source of the expression 'the life of Riley' has been the subject of much etymological research, which had pretty much drawn a blank until the miracle of modern-day searchable databases came to the rescue.

The source of the expression 'the life of Riley' has been the subject of much etymological research, which had pretty much drawn a blank until the miracle of modern-day searchable databases came to the rescue.

A scan of a copy of the newspaper the Dublin Weekly Nation, Saturday 14 October 1899 shows that Reiley (and as it turns out it is Reilly, not Riley) was the hero of a popular folk ballad, living exactly the life that would lead to the coining of the phrase we have been seeking.

The lyric of the ballad is preceded by a reminiscence of the Irish nationalist politician Sir Charles Duffy:

Willy Reilly, says Sir Charles Duffy, was the first ballad I ever heard recited, and it made a painfully vivid impression on my mind. I have never forgotten the smallest incident of it. The story on which it founded happened some sixty years ago; and, as the lover was a young Catholic farmer, and the lady's family of high Orange principles, it got a party character, which, no doubt, contributed its great populanty.

If we believe Duffy's account that Willy Reilly was a living, breathing 1820s Irishman, then we have our man.

Duffy goes on to indicate the widespread knowledge of the song in the north of the island of Ireland:

"There is no family under the rank of gentry in the inland counties of Ulster where it is not familiarly known. Nurses and semptresses [seamstresses], the honorary guardians of national songs and legends, have taken it into special favour, and preserved its popularity."

Here's the ballad, as printed in 1899, which recounts the story of Willy Reilly running away with his hieress lover only to be caught and tried for abduction, eventually finding freedom and riches in his lover's arms - truly the life of Reilly:

[Note: 'Coolen bawn' is an Anglised version of 'Caillin ban', meaning 'young, white girl'. The original 'ban' would make sense in the rhyming scheme, which rhymes it with 'land', 'band' etc.]

"Oh! rise up, Willy Reilly, and come along with me,

I mean to go with you and leave this counterie,

To leave my father's dwelling, his houses and free land;"

And away goes Willy Reilly and his dear Coolen Bawn.They go by hills and mountains, and by yon lonesome plain,

Through shady groves and valleys all dangers to refrain;

But her father followed after with a well-arm’d band,

And taken was poor Reilly and his dear Coolen Bawn.It's home then she was taken, and in her closet bound.

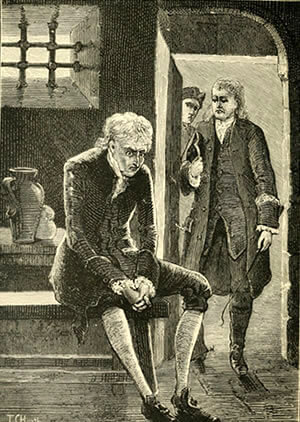

Poor Reilly all in Sligo jail lay on the stony ground,

'Til at the bar of justice before the Judge he'd stand.

For nothing but the stealing of his dear Coolen Bawn."Now the cold, cold iron hands and feat are bound.

I'm handcuffed like a murderer, and tied unto the ground.

But all the toil and slavery I’m willing for to stand,

Still hoping to succoured by my dear Coolen Bawn."The jailor’s son to Reilly goes, and thus to him did say,

"Oh! get up, Willy Reilly, you must appear this day.

For great Squire Foillard's anger you never can withstand,

I’m afeared you'll suffer sorely for your dear Coolen Bawn.""This the news, young Reilly, that last night I did hear,

The lady's oath will hang you or else will set you clear;"

"If that be so" says Reilly, "her pleasure I will stand,

Still hoping to be succoured by my dear Coolen Bawn."Now Willy's drest from top to toe all a suit of green,

His hair hangs o’er his shoulders most glorious to seen;

He's tall and straight, and comely as any could found,

He's fit for Foillard's daughter, was she heiress to a crown.The Judge he said, "This lady being in her tender youth,

If Reilly has deluded her she will declare the truth;"

Then, like a moving beauty bright, before him she did stand,

"You’re welcome there, my heart’s delight and dear Coolcn Bawn.""Oh, gentlemen.” Squire Foillard said, "with pity look on me,

This villain came amongst us to disgrace our family,

And by his base contrivance this villainy was planned,

If I don't get satisfaction I'll quit this Irish land."The lady with a tear began, and thus replied she,

"The fault is none of Reilly's, the blame lies all on me,

I forced him for to leave his place and come along with me,

I loved him out of measure, which wrought our destiny."Out bespoke the noble Fox, the table he stood by,

"Oh, gentlemen, consider on this extremity;

To hang a man for love is a murder you may see,

So spare the life of Reilly, let him leave this counterie.""Good, my lord, he stole from her her diamonds,

Gold watch and silver buckles, and many precious things,

Which cost me in bright guineas more than five hundred pounds,

I'll have the life of Reilly should it cost ten thousand pounds.""Good, my lord, I gave them a token of true love,

And when we are a parting I will them all remove.

If you have got them Reilly, pray send them home to me."

"I will my loving lady, with many thanks to thee.""There is a ring among them I allow yourself to wear,

With thirty locket diamonds well set in silver fair,

And as a true-love token wear it on your right hand,

That you'll think on my poor broken heart when you're in foreign lands."Then out spoke noble Fox, "You may let the prisoner go,

The lady's oath has cleared him, as the Jury all may know

She has released her own true love, she has renewed his name,

May her honour bright gain high estate, and her offspring rise to fame."

This is clearly a romanticised ballad and there are several variants of it, so we need to proceed with caution. In favour of it being a true account of real events, there was a wealthy Protestant Ffolliott family living in Sligo at the end of the 18th century and also a Luke Fox, who was a magistrate in the area at that time. There are also historical accounts of a minor landowner called Reilly, living nearby in county Sligo, who set his sights romantically on Helen Ffolliott, the daughter of the house and who was tried in the manner the song suggests. So, there's good circumstantial evidence that the major characters referred to in the ballad were real people.

Counting against the veractiy of the story is the fuzziness of the date and location. The details of the story, and of the ballad, appear in several variants. Duffy's account for instance places Reilly as living in the 1820s, not the late 18th century.

Nevertheless, the thrust of the tale is consistant amongst the versions of it, that is, Reilly wooing/abducting Ms Ffolliott and later being united with her and her wealth and contentedly raising a family together. Some variation of the retelling of a romantic folk tale is to be expected (in Ireland more than in most places) and, all things considered I would say that the best contender we have as being first person to live 'the life of Reilly' was Willy Reilly of Sligo, Ireland.